The grand unified theory of Batman

Listen very closely, because I'm about to tell the world the definition of a great Batman comic. And I'm also going to explain why The Killing Joke is not a great Batman comic.

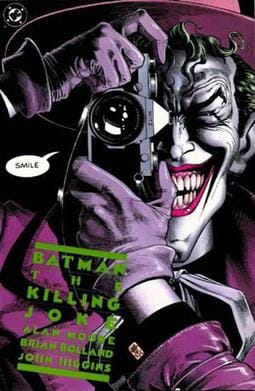

The Killing Joke has had a disproportionate effect on my life. It's the story that made me a comics fan (as opposed to a Spider-Man fan, which is what I was before). I read it when I was, I think, about ten, because my brother had a copy. It's probably the single comic that has everything ten-year-old me could have wanted: it's so cynical and nasty, it's incredibly stylish with those scene transitions and opening and closing slow pan to a closeup of a raindrop splash, it has amazing Brian Bolland art and it's about a grown man dressing up as a bat and fighting a clown.

But as time passed I came to believe that it's not a good story about bat-themed vigilantism, and it took me years to figure out why. Alan Moore has given numerous interviews about his dissatisfaction with The Killing Joke where he says things like "it doesn't tell you anything except that Batman and the Joker are mirror images of one another" but that doesn't really resonate with me as a criticism.

No. Here's the problem. The story of Batman is at its heart the fantasy of a five-year-old boy. It's "a bad man hurt me so I'm going to become badder and scarier than everyone else and nobody will be able to hurt me again." And you should be able to explain the bare bones of any essential Batman story on exactly that level. You can do it with The Dark Knight Returns: "Batman retired years ago but now the world needs him again so he comes back." Batman: Year One is the origin story from the comics, so no problem there (yes, more adult things have been added around the edges, like how Catwoman is now a sex worker, but the story doesn't turn on that).

You can do this with Mad Love: "the Joker's sidekick tries to impress him by killing Batman." Blades: "a man who reminds Batman of his childhood hero Zorro comes to Gotham to fight crime." JLA: Tower of Babel: "Batman has been making plans for how to beat the rest of the Justice League if they turn evil, and a bad guy gets hold of the plans." And so on.

So let's try this with The Killing Joke: "The Joker wants to prove that everyone is like him really so he assaults and victimises and paralyses Commissioner Gordon's daughter and then puts the Commissioner on a funfair ride and shows him the photographs to try and drive him…" and my imaginary five-year-old has already lost interest and gone off to read something like Knightfall, which is a far less accomplished comic but which doesn't do violence to the core concept of what a Batman story is.

Interestingly, the one great Batman comic that doesn't seem to fit this theory is Gotham Central, which for those of you who haven't read it is a police procedural set in Gotham City, sort of like Homicide: Life on the Street if those cops had to face off against the Riddler and deal with occasional cameo Batman appearances. You can't boil down those stories to be five-year-old friendly. But ultimately those are crime procedurals with a dash of Batman flavouring. They're really Gotham stories, like the recent HBO Penguin series where Batman never shows up at all. I'm not sure to what extent writers Greg Rucka and Ed Brubaker would agree with this, but I personally feel that if they had widened the narrative viewpoint so that you knew who Batman was and how he came to be it would have made the whole enterprise implode in a cloud of shark-repellent Bat-Spray.

Anyway, now you all know how to write a great Batman story and there is no longer any excuse for not doing it.